|

|||||||||

Engaging in Romantic Relationships Engaging in romantic relationships is developmentally appropriate during young adulthood. 35 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 and almost all youth by age 18 report having dated at some point. Helping young people have healthy romantic relationships may have lasting impacts. Healthy romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood are shown to be associated with more positive well-being outcomes. For example, fewer mental health problems, higher life satisfaction, higher self-esteem, and other positive young adult outcomes such as academic success. Ways to establish the foundation for talking to young people about healthy relationships include:

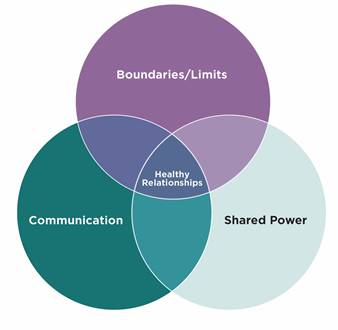

Research and practice literature suggests that a broad array of domains are importantindicators of healthy romantic relationships. Critical domains include: Communication Boundaries/limits Shared power As shown in the following figure, these domains overlap and are all needed to foster healthy relationships. For example, equality and mutual respect are needed for a person to feel comfortable communicating their boundaries and enforcing those limits.

The ways that domains overlap include the following: Overlap of boundaries and communication––Healthy communication is needed to set and enforce boundaries. Overlap of boundaries and shared power––Boundaries can help partners understand how to share responsibility in relationships and work toward equality. Shared Power––Requires a balance of support and responsibilities between their partner(s). Overlap of communication and shared power––In relationships with shared power partners communicate to establish balanced responsibilities/needs/wants. Systemic and cultural considerations Systemic and cultural considerations impact the structure of a relationship and, how these domains are observed and experienced. For example, a systemic consideration may include how gender norms in society influence youths’ view of roles within a relationship, or norms that are specific to a geographic location. Cultural considerations may include religion, immigration status, and ethnic backgrounds, among other factors. Cultural considerations can influence perceptions of relationships and influence expectations and approaches toward understanding their relationships among young people who experience the child welfare and/or justice systems, homelessness, and/or The following list of recommendations is not exhaustive but provides a starting point for talking with young people about healthy romantic relationships:

Dos and Don’ts for Talking with Youth About Healthy Romantic Relationships Components of healthy communication include active listening, honesty, and being aware of non-verbal communication, regardless of whether the communication occurs in-person or electronically. Healthy communication requires youth to be able to express themselves, regulate their emotions, and have a sense of self-awareness. Research finds that healthy communication between romantic partners has a significant impact on individual well-being and relationship quality and satisfaction for young adults. Studies also suggest that youth often struggle to communicate with romantic partners and may lack confidence in their own communication skills. Healthy communication can allow partners to handle stressful situations, manage conflict, apologize when needed, help ensure everyone in the relationship is on the same page, and establish a strong sense of understanding and connection. Communication is a precursor for other components of healthy relationships such as setting and enforcing boundaries and addressing power dynamics. Depending on the cultures they experience young people may vary in the ways they communicate and how those cultures’ use high and low-context communication. High-context communication relies on heavy use of implicit information like body language, eye contact, and tone of voice. Low-context communication norms include using explicit information like words and facts. These differences might lead to miscommunication in partners if one partner uses nonverbal cues and another partner is unaware of those cues. Additionally, different communication styles may not be appropriate for every relationship. For example, a more assertive communication approach, especially for women, may not align with the values and communication patterns within some cultures. Young people who experience the child welfare and/or justice systems, homelessness, and/or disconnection from school and work may need to adapt their communication style to maintain safety in a relationship. For example, an assertive communication approach may not be effective if it increases the likelihood of a negative or violent response from a partner. Youth-supporting professionals should be aware of differences in communication that are shaped by a particular partner, and help youth navigate these differences within their relationships. How to help youth build communication skills to foster healthy, romantic relationships

How to help youth set boundaries/limits Studies show that healthy relationship programming for adolescents generally improves their ability to differentiate between characteristics of healthy and unhealthy relationships, and to recognize the important role of boundaries. In romantic relationships, boundaries constitute individuals’ expectations and limits of what behaviors are acceptable or not acceptable of themselves and their partner(s). Boundaries help youth express to their partner(s) what they need to feel content and safe in a relationship and help their partner(s) understand how they can support the relationship. Setting effective boundaries requires youth to express their own needs and limits and be open to listing and respecting boundaries set by their partner(s). Boundaries are rooted in what individuals find comfortable or uncomfortable and are highly individualistic. Everyone has different boundaries based on their experiences in life and relationships, both romantic and nonromantic. Boundaries can take many forms, but most studies identify 4 main categories: physical, material, mental/intellectual, and emotional.

Healthy relationship curricula and programs have been shown to help youth understand the importance of boundaries and establish limits that support their own needs. Research and practice resources cite communication as the most effective strategy to establish boundaries. Strategies can include partners asking each other clear questions about what they are/are not comfortable with and, however, resources on healthy relationships recommend holding others accountable by clearly communicating when a boundary is crossed, the consequences for crossing a boundary, and following through on that consequence. Relationships may be unhealthy if a young person’s boundaries are ignored, minimized, or disrespected by a partner. Systemic and cultural considerations for setting and enforcing boundaries in healthy, romantic relationships Norms associated with boundary-setting vary across cultures. For decades, research has explored how growing up in either collectivist or individualist cultures impacts one’s expectations of themselves, their partner(s), and others (e.g., parents, caregivers, family members, friends) in romantic relationships. For example, if one partner grew up in a collectivist culture, they may expect to spend most of their time with their partner(s) and do things together, whereas someone who grew up in an individualist culture may want more autonomy and independence in Suggestions on how to help youth set and reinforce boundaries in healthy, romantic relationships:

Shared Power Healthy relationships require equity. Equity, reciprocal and shared power, including support, respect, and personal agency helps prevent negative relationship outcomes such as dating violence. Elements of equity within relationships include an equitable provision of support between partners, a sense of fairness, and mutual respect. Young adults who have more mutuality—or consideration of the needs of others as well as one’s own needs—tend to feel more secure and satisfied in their relationships and better mental health. Lower satisfaction with the division of decision making in a relationship is a risk factor for negative relationship outcomes, including victimization by one’s partner. Existing societal inequalities or differences in life and romantic experience levels can create power dynamics that challenge equity in relationships. Many youth experience a real or perceived disadvantage to their power within a romantic relationship. These power dynamics may include situations where partners have 1) a large gap in age or experience in romantic relationships; 2) differences in wealth, income, or the stability of their living situation; and 3) differences in social networks and support (e.g., if one partner is not “out” to colleagues, friends, or family). Such power imbalances can make one partner susceptible to unhealthy relationship dynamics such as unhappiness and lower trust, increased sexual risk behaviors, or even threats to their well-being (e.g., dating violence). Power differences do not exist in isolation; they exist in the context of gender inequity, bias against LGBTQ+ relationships, and racism in society. For example, even among adolescents who profess that they want to be in a gender equal relationship, adolescents face pressure to fill gendered roles: e.g. masculine toughness and sexual experience, feminine caretaking and controlled sexual availability. When adolescents hold more gender-egalitarian beliefs, they endorse fewer harmful myths about romantic relationships, experience less hostility and violence, and have higher overall relationship quality. Discussing equity in relationships may be a difficult subject. Adolescents may feel self-conscious or defensive about an unequal or power-imbalanced relationship they are in. Youth-supporting

Dos and Don’ts for Talking with Youth about Healthy Romantic Relationships

Based on the evidence-based practice tools on healthy relationships identified in this summary, youth-supporting professionals may need additional tools for working with young people who experience the child welfare and/ or justice systems, homelessness, and/or disconnection from school and work. The tips for working with youth presented here are a starting point for these conversations. References: Information and text language for this report has been taken from the following publications: Rosenberg, R., Naylon, K., Rust, K., Beckwith, S., & Woods, N. Healthy romantic relationships and youth well-being. Child Trends. 2024. https://activatecenter.org/resource/healthy-romanticrelationships- Rosenberg, R., Naylon, K., Simone-Woods, N., Rust, K., Beckwith, S. Crucial Conversations about Healthy Romantic Relationships: A Toolkit for Youth Supporting Professionals. Child Trends. 2024.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||